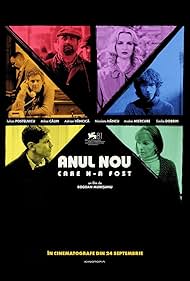

– of director Bogdan Muresanu

Chronology

In 1989, on the brink of revolution in Romania, six lives intersect amid protests and personal struggles, leading to the explosive fall of Ceausescu and the communist regime. “The New Year That Never Came” tells the stories of the last two days of unfreedom for Romanians. It is, incredibly, the first feature film – at the age of 50! A solid, mature, moving film and a history lesson for Romanians – alas, too many – who do not know or have forgotten the past of the communist dictatorship.

Even when foreign radio stations announce the demonstrations that have started in Timisoara, nothing seems to be moving in Bucharest

In my opinion, in the history of Romanian cinema, it is an important film, as was “Reconstitution” by Lucian Pintilie from 1970. It was only the second film by the most important Romanian theater and film director of the second half of the 20th century. The action of “The New Year That Never Came” The film takes place on December 20 and 21, 1989, at the end of the communist dictatorship. The characters in the film, like most of those who lived through that time, have neither the feeling nor the hope of being able to experience the change that is about to happen, the fall of communism that has already happened in almost all Eastern European countries.

A Securitate officer manipulates his informants who monitor the lives of students and intellectuals

The secret police of the Securitate seem all-powerful, the propaganda machine is running at full speed, life full of shortages and dominated by fear continues. He also has a mother who is about to be evicted from the house she has lived in all her life, which will be demolished to make way for grandiose buildings in the new city center. A television crew has to urgently change a New Year’s Eve tribute to the dictatorship, in which an actress who had fled to the West appears in the foreground, in a situation reminiscent of Mungiu’s collection of short films “Memories of the Golden Age.” The replacement actress has a crisis of conscience when she is forced to participate in the show. A family enters into crisis after learning that their eight-year-old son has asked in a letter to the communist version of Santa Claus to see Uncle Nicu dead, “because that’s what Dad wants.” The television director’s son plans to flee the country with a friend by crossing the Danube, the border with Yugoslavia.

Will the mamaliga (Romanian polenta) explode?

To the music of Ravel’s Bolero, the narrative shots alternate, the tension rises, the boiling point approaches. I found the narrative construction excellent. At first, the viewer may be a bit confused by the multitude of characters and situations, but soon enough, the common denominator (fear, repressed hope in the struggle with resignation, long-suppressed anger) and the connections between the characters become evident. For those who lived through that time, the settings and the cinematographic style create a sense of immersion in the past.

Several of the resulting films were memorable

All the actors are great, but I can’t help but mention three names: Iulian Postelnicu (who had leading roles in at least three good films I saw last year), Adrian Vancica and Nicoleta Hancu. I found the reconstruction of those last days and hours of the dictatorship impressive, with only one major flaw related to the final scene, that of the gathering in Palace Square, where a fictional intervention in the key detail of the beginning of the demonstration that changed history gives way to a revisionist interpretation. Romanian cinema has been returning, repeatedly, for 35 years now, to the last years of the dictatorship and even to the days when Romania’s destiny changed.